Imagine a village earth where harmony is the foundation. Not a utopia, but a place where everyone makes the best of their connectivity.

A community that achieves a truer being through the integration of diversity and different identities; where the goal is for people to work to understand each other. Where everyone treats all life, friend or foe, with courtesy, compassion, and kindness. A place with solidarity of the human family.

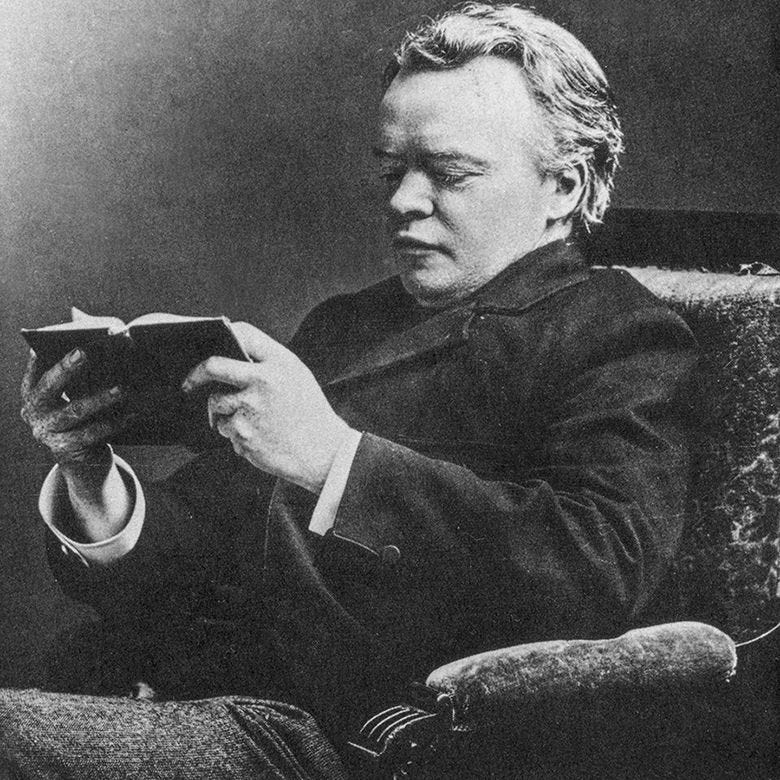

In the early 1900s, the philosopher Josiah Royce (1855-1916) hypothesized a place like this. He called it the beloved community.

Royce was a Californian native, who in his 20s, went to Heidelberg and Leipzig to study German philosophers such as Hegel, Kant, and Fichte. While there he became friends with the orientalist, Charles Lanman, who got him into studying the Bhagavad Gita as well. He returned to California and became a professor at the University of California, but found himself without an intellectual community of philosophers. William James said at the time that “Royce was the only philosopher between Bering’s Strait and Tierra del Fuego.” Eventually an opportunity opened up at Harvard and Royce relocated there in 1882. Within a few years, he published his first book, The Religious Aspects of Philosophy.”

By the late 1800s, Royce had amassed a body of written work and was called to conduct The World and the Individual lectures at Harvard. At these lectures Royce presented his philosophies of the individual and his vision for humanity. One of Royce’s key points in these lectures was that “reality was spiritual and that reality consisted of one unified thing - the Absolute - of which all individuals were a part.”

Though he had been away from California for a long time, it stayed on Royce’s mind. “Royce was deeply interested in California, especially in the problem of how in a community, different races can live together side-by-side, in a peaceful and interdependent manner. In 1908, he wrote Race Relations, Provincialism and Other American Problems. This work covered the Japanese immigrants and their Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, as well as the Chinese immigrants whose labor had built the railroads.”

Towards the end of his career, a lifetime of thoughts came together to be called beloved community.

In Josiah Royce’s 1913 book, The Problem of Christianity, he speaks of ones “loyalty” and “practically devoted love” to their community. To Royce, individuals were also part of a greater “organism”.

In the 1950s, Dr. Martin Luther King resurrected this term, combining it with other similar ideas and popularized it through his sermons and approach to non-violent protest.

“Beloved community was a goal. It was the best of everyone, working for the best of all humanity, and encompassing all of humanity. It starts with a community loyally working toward that end, ever expanding -- the enlargement of the ideal community of the loyal in the direction of identifying that community with all mankind." Rev. Crawford

“King saw the participants in the Civil Rights movement as representing the beloved community in microcosm.” Kenneth L. Smith and Ira G. Zepp, Jr.

For Dr. King, the Civil Rights movement was a quest to becoming mankind of the future. It brought forth a model for how we can live and thrive together.

In 1957, writing in a Southern Christian Leadership Conference newsletter, Dr. King spoke of the purpose and goal of that organization: "The ultimate aim of SCLC is to foster and create the ‘beloved community’ in America where brotherhood is a reality. SCLC works for integration. Our ultimate goal is genuine intergroup and interpersonal living -- integration."

He continued to write about this and in his last book he stated: "Our loyalties must transcend our race, our tribe, our class, and our nation”

“King’s was a vision of a completely integrated society, a community of love and justice wherein brotherhood would be an actuality in all of social life. In his mind, such a community would be the ideal corporate expression of the Christian faith.” Kenneth L. Smith and Ira G. Zepp, Jr.

This beloved community vision is much like agape love. “It is a love by which the individual seeks not his own good, but the good of his neighbor. Agape does not begin by discriminating between worthy and unworthy people, or any qualities people possess. It begins by loving others for their sakes...Agape makes no distinction between friends and enemy; it is directed toward both.”

The impact of Dr. Kings words on Frank Hayden

Around the time when Dr. King was becoming a national voice, Frank Hayden was in his junior and senior years at Xavier University of Louisiana in New Orleans. These would be the years that Hayden would produce his first commissions. He would soon graduate, pursue studies at the University of Notre Dame and then head to Germany to study at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich.

In 1960, after his studies abroad, Hayden settled back in Louisiana. In the fall of 1961, he was recruited by Jean Paul Hubbard to teach at Southern University. This brought him to Baton Rouge. Hayden settled into housing on the edge of campus and took up teaching in the old art building.

At this time, Southern’s campus was a very tense environment. A year prior, a series of non-violent protest had led to violence, unjust incarcerations, and boiling racial relations. Fear and anger was a daily thing. There was great anxiety from the uncertainty of where society was headed and what would be happening next. This was elevated more by the constant presence of international media amplifying what was going on at Southern and in Baton Rouge.

Hayden soon found himself having to be a big brother mentor to his students who were trying to come to terms with how to react to the turmoil around them. Hayden’s calmness and wisdom shined in these interactions.

To be a black artist in the 1960s, you were increasingly called upon to focus your art on black identity and the struggle for justice. In this, Hayden began to think about how he could create art that addressed the spiritual tensions going on around him. The words of Dr. King and his vision of a beloved community would become a huge source of inspiration. With this, Hayden began to explore art that illustrated the concepts within this philosophy.

This would lead Hayden to feature the theme of unity and beloved community for the rest of his career.

“Let us not forget that all the greatest epochs at the moment of their apogee manifested their spiritual tension in sculpture” Naum Gabo

“Beloved community is formed not by the eradication of difference but by it's affirmation, by each of us claiming the identities and cultural legacies that shape who we are and how we live in the world” Bell Hooks

- Bennet Rhodes

Brought to you by Culture Candy

Photography by Bennet Rhodes

Learn more at FrankHaydenProject.Org

Reading

Rev. Joanna Fontaine Crawford. 2013

canr.msu.edu/news/remembering_dr._martin_luther_king_jr.s_beloved_community

boundlessloveproject.org/beloved-community

Search for the Beloved community: The Thinking of Martin Luther King. Jr. Kenneth L. Smith and Ira G. Zepp, Jr. 1974

Christian Century, April 3, 1974, pp. 361-363

religion-online.org/article/martin-luther-kings-vision-of-the-beloved-community/

Roberts Wesleyan University. Beloved Community

The King Center. The King Philosophy

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Birth of a New Nation" Speech, April 7, 1957

gotquestions.org/absolute-idealism.html

North East Islamic Community Center

islamiccenter.org/what-is-the-purpose-of-spiritual-tension/

skylight.org/blog/posts/what-is-spiritual-distress

Josiah Royce's Ingersoll Lecture

sociology.unc.edu/undergraduate-program/sociology-major/what-is-sociology/

agape-love-origin-uses-religions.

Five defining characteristics of the Beloved Community:

1. Given our shared desire to be peaceful, happy, and safe, the Beloved Community described a practical, realistic, and achievable society.

2. In the Beloved Community, conflict still exists, but it is resolved peacefully, nonviolently, and without hostility, ill will, or resentment.

3. In the Beloved Community, we recognize the interdependent nature of all life, so we appreciate, recognize, and value the inherent worth of all people, animals, and ecosystems.

4. In the Beloved Community, kindness, compassion, and love for all life motivates our actions. We work cooperatively to peacefully end hunger, prejudice, poverty, homelessness, climate change, environmental destruction, factory farming, and violence and injustice of all kinds.

5. In the Beloved Community, the means we use to create change are just as kind and compassionate as the ends we seek. Our commitment to unconditional and all-inclusive kindness and goodwill allows the Beloved Community to become what Dr. King called "an engine of reconciliation.